Boarding School

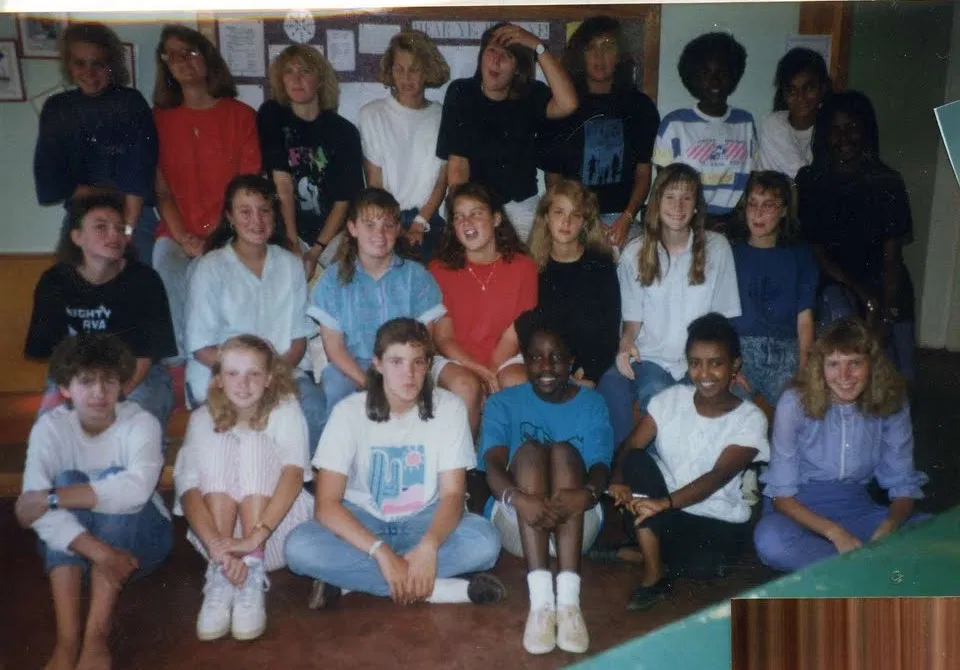

The following is a guest post written by Amy Medina. Amy came to RVA a year after Lilli graduated. The original post appeared on her blog, Not Home Yet. Used with her permission.

Thirty years ago this month, I left my family for boarding school. According to American assumptions, that must mean I was a juvenile delinquent. Or maybe a wizard.

But no, Hogwarts didn’t exist in January 1991 when I was 14, but Rift Valley Academy did. My family had recently moved to Ethiopia, and there was no international high school for me. All the missionary teenagers were sent off to RVA in Kenya, so after a semester of lonely correspondence school, I asked my parents if I could join them.

I wanted to go, but that didn’t mean I wasn’t terrified. I was painfully shy and very much a homebody, and though I had already traveled the world in my short life, I had never been away from my family for more than a couple of days.

I can remember seeing my mother’s tear-stained face through the glass at the airport, trying valiantly to hold it together myself. Though I was traveling with a number of older missionary kids, I didn’t know any of them. It was my first time going through immigration on my own, getting on an airplane, and landing in a country I had never been to before.

A bus picked us up at the airport, and we arrived at the school at dusk. A crowd of kids were there waiting for us, and I saw my suitcase cheerfully carted away by two of the girls from my dorm. There were scads of teenagers, enthusiastically greeting each other after their Christmas “vake,” as they called it, a new vocabulary I knew nothing of. Somehow I managed to be swept along a path, down a set of stairs and into my dorm, where I met the three girls who would be my roommates.

Our room had two iron bunk beds, a large shared desk, four dressers, and a row of four closets. My mom had ordered some sheets, towels, and a blanket for me, which turned out to be pink and green plaid. It was ugly, but I didn’t have a choice. I cried into that blanket every night for the first ten nights.

The depth of my homesickness was intense. My mom and I wrote copious letters to each other, and that was pretty much our only form of communication. Once a month, I had a scheduled call with my parents, but it involved going to another dorm, waiting for an international operator, and trying several times to get through before the connection was made. I missed my family dreadfully, but still, I wanted to stay.

Rift Valley Academy was founded in 1906 and carries with it the mystery and stately dignity of an institution over a hundred years old. It is sprawled on a lush-green compound of rolling hills, the buildings made of brick and wood. The high altitude and the fierce wind make it cold, the view of the Great Rift Valley makes it majestic.

Missionary kids come there from all over Africa. Of my roommates, one family was in Uganda, another in a remote part of Kenya, and the third from Chad. We shared common MK experiences: My story of being exiled from Liberia was no big deal in comparison to what other MK’s had gone through. During the past Christmas break, one roommate’s plane hadn’t been able to land in Chad due to a government coup, so she and her fellow MK’s were evacuated to France for several days. Now that, we all agreed, was exciting. Especially because her fellow evacuees were handsome upper classmen. Who wouldn’t want an evacuation to France with cute boys?

Those three girls and I became friends fast. Looking back, I am astonished at how quickly they accepted this socially awkward, shy teenager into their circle. For the first time, I met girls my age who were thirsty for the things of God. One of them had told me how impressed she was with Elisabeth Elliot’s Shadow of the Almighty. It seemed like such a grown-up book to me; could a teenager really read it? Later, it became one of the most influential books of my life. Together these girls and I formed an accountability group, asking each other weekly how we were doing in our walk with God. We were fourteen. This was mind-blowing to me.

We had an American curriculum, so I read Romeo and Juliet and learned algebra and French. There were basketball games to watch on Friday nights and rugby games on Saturdays. Staff members would host groups of us in their homes for movie nights. Sometimes the whole school would go to a movie showing in the auditorium, and we would watch a “Fresh Prince” episode before the show started. We watched Top Gun once, though with so much of it edited out, even the most tight-lipped missionary would approve.

A popular RVA game, which I later found out went back decades, was called Red Hot Poker. We would clear the furniture in a big room, link hands in a circle, and push, pull, or generally throw each other around in an attempt to get the opposing team to knock over some boxes or a trash can in the center. Kids from California might recognize this game as Kajabe Cancan from Hume Lake Camp. Interestingly enough, Rift Valley Academy is located in the town of Kijabe, Kenya. Is there a connection? Somebody please tell me there is.

Every piece of clothing had my name stitched in it, and every week we had a laundry drop off day and a laundry pick up day. But the girls would buy our own soap and wash our white things by hand in the bathroom sink, because we didn’t want them to come out pink. We also would buy candy and chips at a little shop, which would compensate for the days they served spaghetti casserole or shepherd’s pie at the cafeteria.

For the first few weeks, I helped myself to hot chocolate every morning at breakfast, which was served in plastic cafeteria glasses. Later I found out that it wasn’t actually hot chocolate, but tea with milk, which explained why the hot chocolate always tasted so funny. I was a picky eater, so cafeteria food did not excite me, though the biggest source of weight-loss was when I got amoebic dysentery and had to spend ten days in the infirmary. The nurse who took care of me brought me strawberries and showed me pictures of her grandchildren.

Back in Ethiopia, war was brewing, and all the Ethiopia MK’s were called out for meetings with increasing frequency. In May, my mom and my brother were evacuated. My dad stayed behind and waited for me to finish my school year in July. For about six weeks, the four of us were in three different countries. We returned to the States indefinitely that July, so my time at RVA lasted only six months. I entered a regular high school in California. Very few of my classmates knew that I had just come from boarding school in Africa.

As strange as this may all sound to the average American, I wanted to go to RVA because in my world, this all was considered normal. Missionary kids going off to boarding school was routine. In fact, part of the reason I rarely have written about this is because it all felt rather ordinary. For my fellow missionary kids, spending six months at boarding school is unremarkable. Certainly not worth writing about.

I did eighth grade in America, and then tenth grade through my senior year. My freshman year, with all of its upheaval in Ethiopia and Kenya, was like a lightning bolt of extraordinary circumstances in what would otherwise have been a normal American teenage life. I was now complicated. Aside from my high school advisor having a hard time trying to put together my transcript, I saw the world differently from my peers. I was an American girl, but I agonized over the famine in Sudan and the genocide in Rwanda, and of course, the war in my beloved Liberia. I had no idea how to communicate this to my American friends. My roommates continued to write letters to me throughout the rest of high school, feeding my missionary-kid soul. I desperately needed that.

But in many ways, my time at boarding school is what grew me up, made me brave. Or at least, braver. I was an MK who didn’t have an adventurous bone in her body, who was intensely intimidated by America and its teenagers. I wonder if I would have had the courage to be involved in cross-cultural ministry in high school, the passion to do missions in college, the drive to live in East Africa after college….if I hadn’t gone to boarding school.

Parents in general, but perhaps missionary parents especially, struggle with wondering how much they can ask their children to bend, yet not wanting to break them. I look at that year and consider how much that bending served me, stretched me, matured me. I’m grateful it is a part of my story.